December 6, 2017 | The New York Times

By Frances Robles and Sheri Fink

SAN JUAN, P.R. — For an overburdened pediatrician trying to care for a child who was in pain, needed hip surgery, and was displaced from his home in the wake of Hurricane Maria, it seemed a godsend — a modern military hospital ship sent from its berth in Virginia to help with medical care in Puerto Rico.

But after days calling phone numbers that did not work and trying to navigate the admissions process for the ship, the 894-foot U.S.N.S. Comfort, Dr. Jorge Gabriel Rosado finally gave up. The boy is still awaiting surgery, which had been scheduled for the day before the storm hit more than two months ago.

Staffed with 800 medical personnel, the hospital ship admitted about 290 patients.

“It was rough because there were a lot of people that could have taken advantage of all the resources the Comfort had,” Dr. Rosado said. “But there were so many steps to it. Most physicians on the island, even us, decided it was too many steps.”

The Comfort’s mission has ended, but it leaves behind questions about whether it was adequately used during a time of desperate medical need. The ship was prepared to support 250 hospital beds, but over its 53-day deployment, which included travel to and from the island, it admitted an average of only six patients a day, or 290 in total. An additional 1,625 people were treated aboard the ship as outpatients, all at no cost.

In many ways, the Comfort’s story is that of the wobbly recovery effort in Puerto Rico, in which attempts to bolster vital services have often fallen flat or become entangled in bureaucracy and politics.

Following public debate over the Trump administration’s initial reluctance to deploy it, the Comfort arrived two weeks into the disaster, after some of the medical urgency had abated. Its mission and capabilities were opaque to many doctors on the island. It lacked the ability to treat some important areas of need, and the complex referral procedures made little sense on a battered island with scant power or telephone service.

The result, combined with the reluctance of some hospitals to lose their own patients, fell far short of what the Comfort could have provided, medical experts said.

“They were prepared for anything other than the reality of Puerto Rico,” said José Vargas Vidot, a doctor and independent senator in the Puerto Rican Senate whose charitable organization, Iniciativa Comunitaria, supported the post-hurricane medical clinic directed by Dr. Rosado. “It was like a vision in the harbor. Everybody was looking at the Comfort, like trying to build hope. But in the reality it was very frustrating to get access.”

Staffed with 800 personnel and costing $180,000 a day, the ship received an average of 36 people a day as outpatients or inpatients. (A New York Times reporter was one of them, given an X-ray and medicine for an asthmatic cough). And that number swelled only after a public furor erupted over the ship’s empty beds.

“That’s not the right question,” said Capt. Kevin Buckley, the commander of the ship’s medical facility, when asked how many patients were admitted. The right question, he said, was: “What kind of patients do you have?”

The patients who arrived in the early weeks “were as sick as the sickest patient in any I.C.U. where I’ve worked,” said Capt. José A. Acosta, the United States Third Fleet surgeon, a Puerto Rican-trained physician who served as a liaison with the Comfort.

In all, 191 surgeries, including 25 major orthopedic cases, were performed aboard the ship. Doctors delivered two babies and diagnosed seven people with cancer. One woman had a double mastectomy, and the ship filled the oxygen tanks for dozens of patients who needed help breathing. It took in some patients from hospitals where generators had failed. It treated 98 critically ill patients, eleven of whom died.

The Comfort’s deployment was not the only federal health care initiative after Maria hit. Federal field hospitals, clinics and medical shelters saw more than 30,000 patients, and more than 1,400 uninsured people filled their prescriptions at pharmacies for free thanks to a federal reimbursement program.

A mid-November visit to the ship found dozens of people waiting to see doctors in the tents set up outside, but inside most of the beds were empty. Only a handful of patients were on board, and most of the doctors were milling about.

But those who were getting treatment appeared satisfied. Olga Quezada’s knee had swollen up as if someone had pumped air into it. She had been turned away by her local hospital, and she worried about the pain, the bill and finding care.

Ship doctors stuck a frighteningly long needle into her knee to drain the fluid, for free. “At first, I went to hospital in Bayamón, and they told me to come back,” Ms. Quezada said. She added: “I really like the doctors here.”

The Comfort is used on relief missions about every two years. It served off the coast of Kuwait during Operation Desert Storm in 1990 and 1991 and provided aid during the rescue of Cuban and Haitian migrants in 1994. The Comfort was deployed in Manhattan after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

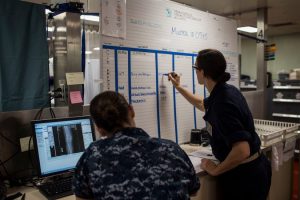

Medical staff took a blood sample from a patient in the emergency room aboard the Comfort. Credit Dennis M. Rivera Pichardo for The New York Times

In Haiti after the 2010 earthquake, the Comfort provided much-needed surgical care, but communication with referring doctors and with family members was problematic. Some patients died during laborious, multistep transfers, and some doctors felt the ship left too soon.

Doctors in Puerto Rico said the Comfort could have been of enormous help directly after the storm, because at first many hospitals were damaged or shuttered.

Without air-conditioning, temperatures soared dangerously, and operating rooms were closed as generators failed. Emergency room staff sewed wounds, lanced boils and examined patients by the light of cellphones and flashlights. They lacked access to CT scans. In the 10 days after the Sept. 20 storm, the number of deaths in Puerto Rico jumped to an average of 118 a day, 36 more than usual.

But the ship did not leave Virginia until Sept. 29, arriving in Puerto Rico on Oct. 3.

Problems quickly emerged. For starters, the Comfort lacked critical capacities, including the ability to treat premature babies and patients with common antibiotic-resistant infections, head trauma and strokes requiring neurosurgery, or heart conditions needing bypass surgery. One doctor was heard complaining about receiving so-called “social cases”— patients who would be difficult to discharge because they lost their homes or lacked caregivers.

When the ship docked in San Juan, residents were thrilled. “People saw the big, white ship and came running,” said Murad Raheem, a regional emergency coordinator for the Department of Health and Human Services who oversaw the federal government’s health response to the disaster.

The Comfort cared for 67 patients in its first two days, but wasn’t set up to receive unscreened patients, Mr. Raheem said.

Soon after the ship’s arrival, Puerto Rican and federal officials and local medical professionals met on the Comfort. They decided the ship should move around the island to assist “wherever the needs were at the time,” Mr. Raheem said.

But they agreed that doctors around the island would need to vet potential patient transfers through the Puerto Rico Medical Services Administration, the large and overburdened public hospital in San Juan that normally served as a referral center. Only if the hospital was full would a case be reviewed for possible referral to the Comfort.

Patient flow slowed to a trickle. According to the Navy, only 137 patients were delivered over a period of three weeks.

The first phone numbers provided by the public hospital did not work, and others had to be established. Callers overwhelmed the cellphone of the emergency department director after his number was posted on Facebook.

In areas without working cellphones, land lines or satellite phones, and with only ambulance radios to communicate, “referring patients to the Comfort was impossible,” said Dr. Rene Purcell-Jordan, an emergency room physician in Yauco, in southwest Puerto Rico.

Dr. Purcell and other doctors said they also had little information about what type of patients the Comfort could or would treat.

Some problems were beyond the Comfort’s control. Poor weather grounded helicopters. Some local hospital administrators were reluctant to give up their patients, and sometimes patients themselves wanted to stay near home, even when conditions at their hospitals appeared dangerous.

Gov. Ricardo A. Rosselló petitioned for changes. He said the ship’s roving mission was appropriate immediately after the storm when roads were impassable, but that as time passed it made more sense to allow seven hub hospitals to refer patients directly and ultimately for patients to refer themselves.

The Comfort returned to the port in Old San Juan. This time, federal Disaster Medical Assi

In all, 191 surgeries, including 25 major orthopedic cases, were performed aboard the Comfort. Doctors delivered two babies and diagnosed seven people with cancer. Credit Dennis M. Rivera Pichardo for The New York Times

stance Teams set up in tents outside the ship, and thousands of people went for prescriptions and care. Those who needed something the tents could not provide, like surgery or X-rays, were taken on to the ship.

“No one who walked up to the ship has been denied care,” Captain Buckley said.

Officials at the public hospital defended the Comfort’s operation.

“The Comfort was not a party boat,” said Dr. Carlos A. Gómez, the head of the hospital’s emergency room. “You need criteria to go to a hospital, whether it’s at sea or on land.”

Still, the mission to the end remained murky. On Nov. 15 the Comfort left the dock, with a spokesman saying the ship planned to restock at sea and then resume treating patients. On Nov. 17, the ship was ordered home, for good, without warning.